21 Dec 2012

Winston Churchill famously described Russia as “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma”. But he also declared the key to understanding it was Russian national interest.

And so it is with Dow Chemical’s latest contribution to the natural gas debate (“Gas industry responsible for market fizzer”, The Australian, December 6). The key to understanding it is self-interest.

There is nothing wrong with self-interest. It is what makes a market economy work. But when it is dressed up as the national interest, it bears closer scrutiny. Dow Chemical’s catch-cry is now that the gas market has failed, not that manufacturers want domestic gas on special terms or resources “nationalism”.

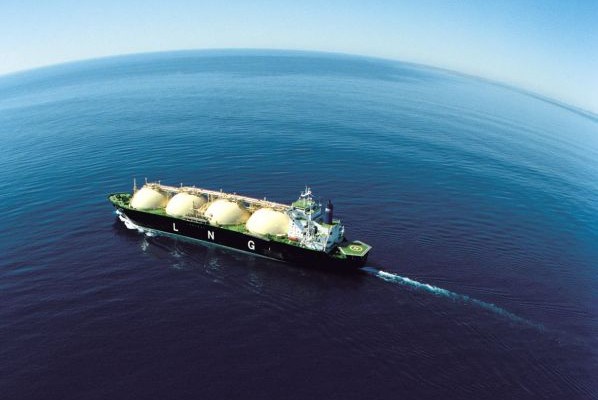

For support, it calls upon a decade-old Council of Australian Governments (COAG) report. In 2002, Australia had one operating liquefied natural gas (LNG) project. Since then, two further LNG projects have been commissioned and seven more are under construction. The current LNG capital investment of more than $200 billion makes up 35 per cent of all Australian business investment.

Why has this happened?

Having gas resources was clearly a prerequisite. Australia has sufficient natural gas from sandstones and coal seams to meet domestic and export needs for over 100 years. And that doesn’t include natural gas from shale, which shows great promise.

But developing these resources requires demand, economic incentives, technology and capital.

Over the last decade, there has been a massive increase in Asian demand for LNG bringing prices linked to international markets. Today’s impressive rate of development of our gas resources has been driven by LNG market opportunities and facilitated by technology enhancing the economic recovery of oil and gas in challenging locations. Capital attracted by these opportunities for reward is funding some of the most complex and expensive projects ever undertaken in Australia.

Yet, even given these advantages, cost competitiveness remains a challenge for Australian gas projects.

Natural gas remains important for domestic industrial and residential consumers and power generation, but the driver of growth has been export opportunities. The key to meeting future domestic and export needs is to prioritise development of Australia’s gas resources. Last week’s report by the Australian Energy Market Operator came to this conclusion. And last month’s Energy White Paper similarly found “no clear evidence at this time to suggest market failure or that our gas markets cannot deliver the necessary supply.”

It’s not the first time that “market failure” claims have been made during commercial negotiations about the terms of domestic supply, such as volumes, price, duration and starting dates. Like all other commercial negotiations, this should be left to the buyers and sellers.

Proponents of Australian gas reservation applaud the US shale gas experience. But how did the US come to have such abundant gas production and such low gas prices (currently around US$3.50/million British thermal units)?

Between 2002-2008, US gas prices tripled, peaking at over $13 in July 2008. This gave the incentive for a massive exploration boom. At its peak, about 1500 rigs were drilling for shale gas. Moving gas to the big US domestic market was facilitated by an existing and extensive pipeline network, limiting the need for additional infrastructure, which reduced development costs. Rapid commercialisation allowed prices to fall to where they are today; not interference with commercial incentives for gas producers.

Meanwhile, the argument for resources nationalism has just been undermined in the US. Earlier this month, the US Department of Energy (DOE) produced a report that finds net economic benefits from America exporting shale gas (as LNG). What’s more, those benefits would increase as the LNG market grows: “Scenarios with unlimited exports always had higher net economic benefits than corresponding cases with limited exports.”

Australia is already enjoying the national benefits of LNG industry growth and they are no flash in the pan. Analysis by Deloitte Access Economics finds currently committed oil and gas projects can deliver $612 billion value added (in net present value terms) to the Australian economy between now and 2035. More aggressive investment and development can deliver more than $800 billion value added over the same period. This creates jobs, opportunities for local businesses and service sectors, tax revenues and higher real income for Australian households.

It’s not surprising that the US covets similar benefits from a major export industry. Nor is it surprising that Dow Chemical is criticising the DOE report as “flawed” and “misleading” with “baffling” conclusions.

What is surprising is that a major international company operating in 36 countries and selling to customers in over 160 nations apparently does not support open access to international markets and selling products for their highest market value. For that is what Dow Chemical describes as a “gambling strategy”, when addressing gas policy in Australia.

Dow Chemical says the US manufacturing industry has announced over 100 capital investments representing over $90 billion in spending. This is undoubtedly a success story.

But LNG is also a success story and one that is still in progress.

Australia has $200 billion of LNG capital investment underway in an economy one-tenth the size of that of the US.

LNG is a source of comparative advantage that Australia should harness not hinder. This is not gambling; it is a sensible and proven economic strategy that leverages the benefits of open and competitive international markets.

In all sectors of the economy (not just oil and gas), maintaining access to open and competitive markets is in Australia’s long-term national interest. As Churchill might have said, this is a strategy worth defending, one that Australia should “never surrender”.

David Byers is APPEA’s Chief Executive. This blog post was first published in the Weekend Australian on 22 December 2012.